Try our mobile app

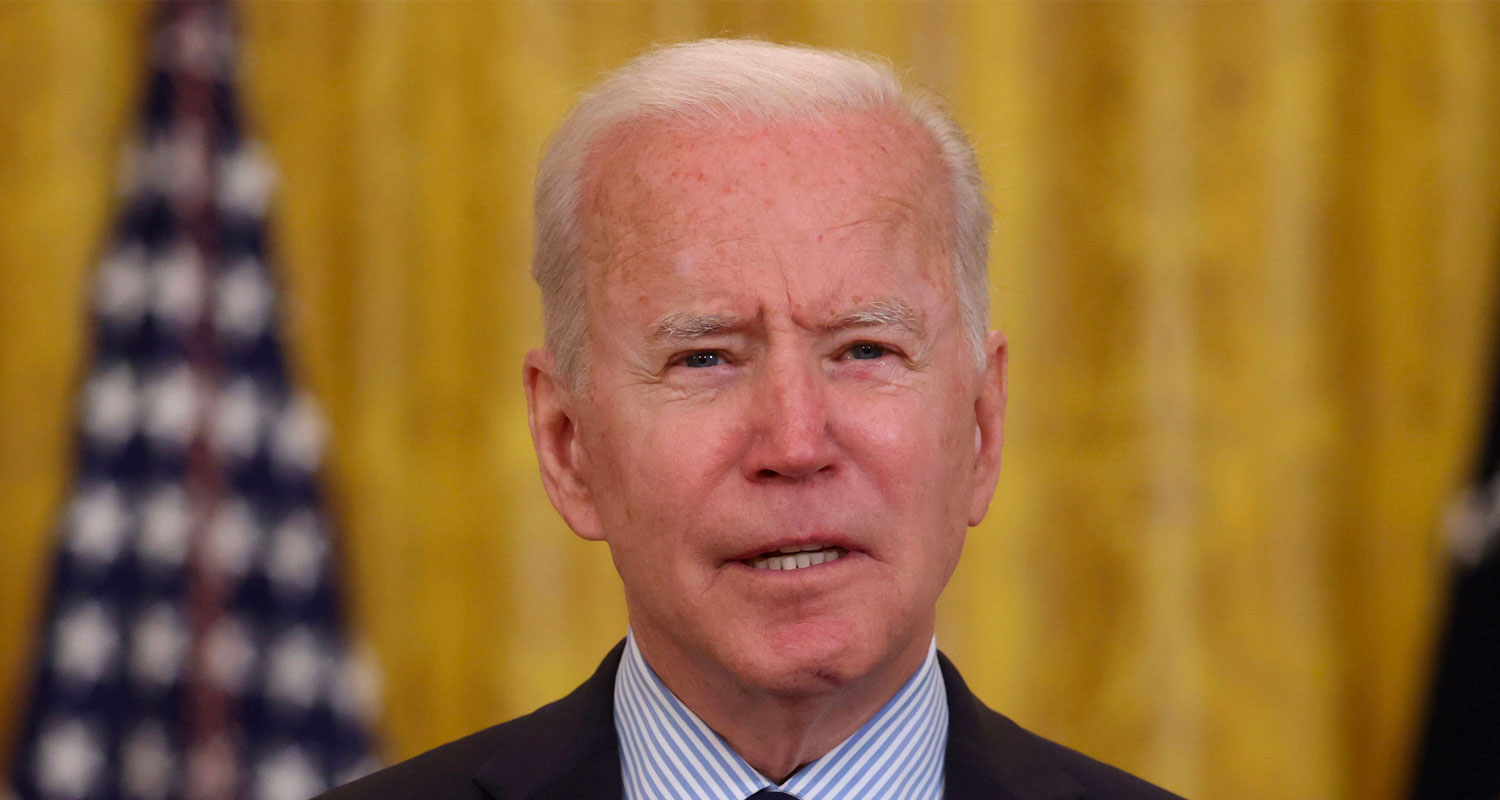

US President Joe Biden Intel is receiving US$20-billion in grants and loans to help finance the expansion of its production capacity in the US, becoming the largest beneficiary by far of the 2022 Chips and Science Act, the cornerstone of President Joe Biden’s plan to reverse a decades-long decline in the US’s share of global semiconductor output. The White House is already trotting out this award on the campaign trail as proof that its policies are working for America, but the reality is that the conditions attached to it just underscores the country’s competitive disadvantages. And while global demand for chips is trending sharply higher, primarily due to breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, the US has neither the workforce capability nor the regulatory regime to keep up. Chip makers are on course to add about 115 000 jobs by 2030, the Semiconductor Industry Association said in July, citing a survey it commissioned, but based on current degree completion rates, about 58% of those projected positions may go unfilled. Even US commerce secretary Gina Raimondo warned in December that US efforts to build out the domestic semiconductor industry could be delayed by years because of the standard environmental reviews. TSMC halted construction on a $40-billion facility in Arizona because of a dispute with the local pipe-fitters union To qualify for the grants associated with the Chips Act, recipients must not only expand production capacity in the US but do so in a way that advances the Biden administration’s larger agenda, from increasing the representation of marginalised workers in the tech industry to coordinating with organised labour on their workforce development plans. Such goals may be worthwhile, but they increase manufacturing costs and make expanding production risky. In the case of Intel, the Santa Clara, California-based company won’t get all of the funding right away. The money may take years to be disbursed and will be contingent upon Intel meeting production goals and other benchmarks. It’s telling that Intel’s shares are little changed since mid-February, when it was revealed that the company was in talks for the funds even as the broader equity markets have soared. Risky proposition The world’s largest chip manufacturer, Taiwan’s TSMC, halted construction on a $40-billion facility in Arizona because of a dispute with the local pipe-fitters union. TSMC, as the company is known, negotiated with the union for six months before reaching a settlement that allowed construction to proceed. TSMC executives told investors the plant would cost four times as much to build in the US as it would have in Taiwan, mainly due to higher labour and regulatory costs. And back in July, the company’s executives said among the several challenges it faced was a shortage of skilled workers. “We are working on improving this by sending skilled technical workers from Taiwan to the US,” chairman Mark Liu said on a conference call at the time to discuss earnings. The possibility of labour disputes, permitting delays and other cost overruns clearly makes building facilities in the US a riskier proposition for chip makers. That means that the impressive surge in construction spending on new factories, which has doubled under Biden, may sputter. America’s cost competitiveness is, if anything, deteriorating, and when the government money runs out, manufacturers may again turn to Asia or other locales where labour is cheap and regulations are low to expand production. Even now, most of Nvidia’s advanced chips are made in Taiwan. Read: China blocks use of AMD, Intel in government PCs That’s a shame because the America’s dominance in AI development means that semiconductors will become even more critical to the US economy, and the risks associated with dependence on imported chips will become even more severe. The US accounts for 34% of global chip demand but only 12% of global supply. The consequences of this imbalance were apparent in 2021 when a worldwide chip shortage during the pandemic brought US car manufacturing to a halt. Some event that leads to another shortage in the future could threaten US leadership in AI. The top AI companies — OpenAI, Microsoft, Google and Anthropic — and Nvidia, the dominant chip maker for AI systems, are all based in America. This is disconcerting given the assessment commissioned by the state department that AI development by US adversaries poses a significant national security threat. So, rather than job creation, national security should have guided the Biden administration’s implementation of and messaging around the Chips Act. Had it done so, the administration could make the case that the sustained expansion of semiconductor manufacturing capacity takes precedence over other economic policy objectives. As things stand, the Chips Act will likely deliver a one-time surge in US production of semiconductors but no lasting reversal of America’s declining share of global output. — Robert Burgess and Karl W Smith, (c) 2024 Bloomberg LP Get breaking news alerts from TechCentral on WhatsApp